An open competitive examination is a public hiring process where anyone who meets basic eligibility rules can apply, and the best candidates are selected based on their performance in standardized tests. It’s not about who you know, who your parents are, or how much money you have. It’s about what you know and how well you can prove it under pressure. This system is used by governments around the world to fill important public roles-from police officers and tax inspectors to judges and top-level administrators.

How Does an Open Competitive Examination Work?

The process usually has three main stages: a written exam, an interview, and sometimes a physical or skill-based test. The written exam is the biggest filter. It’s designed to test knowledge, reasoning, and analytical skills-not memory alone. For example, in India’s UPSC Civil Services Exam, candidates face two preliminary papers covering current affairs, history, geography, and basic math, followed by nine detailed mains papers that dig into governance, ethics, and public policy. Only those who clear the mains are called for the final interview, where their judgment, communication, and personality are assessed.

These exams are often held once a year, with hundreds of thousands applying for just a few hundred spots. In 2024, over 1.3 million people applied for India’s UPSC exam, and only 1,100 were selected. That’s less than 0.1% success rate. The system is tough, but it’s meant to be fair. Everyone gets the same question paper, the same time limit, and the same grading rubric.

Why Do Governments Use This System?

Open competitive examinations exist to prevent favoritism, corruption, and nepotism in public hiring. Before these exams became common, government jobs were often handed out as rewards to political allies or family members. That led to inefficiency, low morale, and public distrust. Countries like China, France, and the UK adopted competitive exams in the 1800s to build professional, merit-based civil services. The U.S. followed with the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act of 1883 after scandals over job appointments.

Today, countries with strong open exam systems-like Singapore, South Korea, and Japan-consistently rank higher in government transparency and public service efficiency. The logic is simple: if you want competent leaders managing your schools, hospitals, and roads, you need to pick them based on skill, not connections.

What Kind of Jobs Are Filled Through These Exams?

Open competitive exams are used for roles that require deep knowledge, ethical judgment, and long-term public accountability. Common positions include:

- Indian Administrative Service (IAS), Indian Police Service (IPS), and other All India Services

- Foreign Service Officers (like the U.S. Foreign Service or UK’s FCDO)

- Revenue officers (tax collectors, customs agents)

- Public prosecutors and judicial assistants

- Senior roles in central banks, statistical offices, and regulatory agencies

These aren’t entry-level jobs. Most require a bachelor’s degree, and many candidates spend years preparing. But once you get in, the job is usually stable, well-paid, and comes with significant responsibility. You’re not just working for a paycheck-you’re shaping public policy.

Who Can Apply?

Eligibility rules vary by country and position, but there are some common patterns. Most exams require:

- A minimum age (usually 21-22 years old)

- A maximum age limit (often 30-32, with relaxations for women, minorities, or disabled candidates)

- A bachelor’s degree from a recognized university

- Citizenship of the country offering the job

Some countries allow candidates from neighboring nations to apply for certain roles. For example, Nepal and Bhutan citizens can apply for some Indian government positions under special agreements. But in most cases, you must be a citizen to qualify.

There’s no limit on how many times you can try. Many successful candidates clear the exam on their third, fourth, or even fifth attempt. That’s why you’ll see 28-year-olds and 35-year-olds sitting side by side in exam halls.

What Makes These Exams So Hard?

The difficulty doesn’t come from the complexity of the questions-it comes from the volume and the pressure. You’re not just studying one subject. You’re expected to know:

- Current events from the last 12-18 months

- Constitutional law and governance structures

- Economic policies and global trade trends

- History of social movements and public administration

- Basic science, geography, and environmental issues

And you have to write clear, well-structured answers in a limited time. In the UPSC mains, you’ll write 15-20 essays and long answers, each worth 10-25 marks, in under 3 hours per paper. That’s about 15 minutes per answer-and you need to include facts, examples, and analysis.

There’s no syllabus you can memorize. The questions are unpredictable. They test your ability to think, not just recall. One year, you might get a question on the impact of AI on rural healthcare. The next, on the historical roots of federalism in your country. Preparation means building a broad, flexible understanding-not cramming notes.

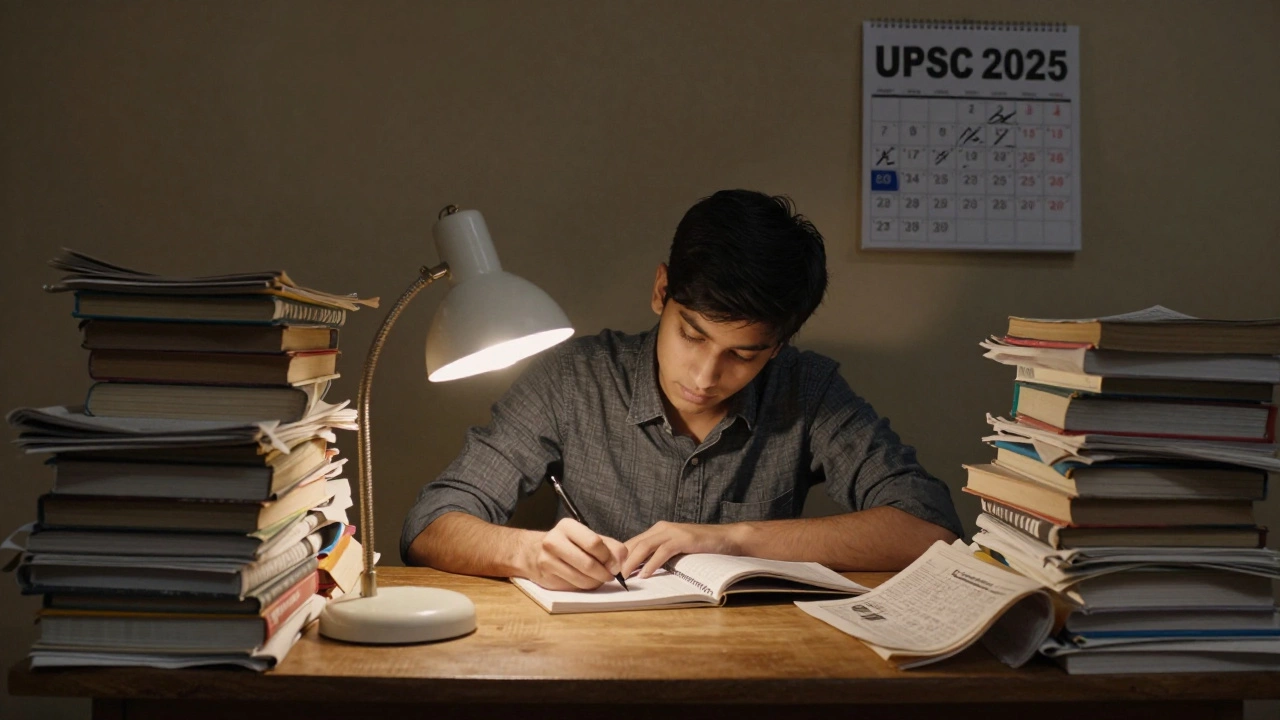

How Do People Prepare?

Most candidates start preparing 12-18 months before the exam. They use a mix of resources: government publications, standard textbooks like NCERTs in India, current affairs magazines, and online video lectures. Many join coaching centers, but others succeed entirely on self-study.

Successful candidates don’t just study-they practice. They write mock answers, get them reviewed, and rewrite them. They analyze past papers to spot patterns. They read newspapers daily-not just for facts, but to understand how issues are framed and debated.

One key habit among top performers: they write daily. Even if it’s just 300 words on a current event, writing trains your brain to organize thoughts quickly. That’s what the exam rewards: clarity under pressure.

What Are the Downsides?

Despite its fairness, the system isn’t perfect. The preparation is expensive. Coaching can cost thousands of dollars. Books, test series, and internet access add up. Many rural or low-income candidates struggle to compete, even if they’re smarter or harder working.

There’s also a mental toll. The pressure to succeed can lead to anxiety, depression, and burnout. In India, there are tragic reports each year of candidates taking their lives after failing multiple times. The system doesn’t account for emotional resilience.

Some critics argue that the exams favor urban, English-speaking candidates who have access to better resources. To fix this, some countries now reserve seats for women, tribal communities, or people from backward regions. Others have started offering exams in regional languages. But progress is slow.

Is It Worth It?

If you’re looking for a job with job security, social respect, and real impact-yes, it’s worth it. The salary isn’t always the highest, but the benefits are strong: pension, healthcare, housing, and the chance to serve your country.

But don’t go in thinking it’s a shortcut to success. It’s a marathon, not a sprint. You need discipline, patience, and the ability to keep going even when you fail. Many who succeed say the real reward isn’t the job title-it’s knowing they earned it, without help or favor.

If you’re serious about applying, start by reading the official notification from your country’s public service commission. Know the syllabus. Know the dates. And most importantly, start writing-every day.

Is an open competitive examination the same as a civil service exam?

Yes, in most cases. A civil service exam is a type of open competitive examination used specifically to recruit government officials. Not all open competitive exams are for civil service-some are for police, judiciary, or public sector corporations-but civil service exams are the most common and well-known form.

Can I take an open competitive examination if I’m not a citizen?

In almost all cases, no. These exams are designed to hire citizens who will serve their own country’s public interest. Some exceptions exist, like in the Gulf states or under regional agreements (e.g., India allows Nepali and Bhutanese citizens to apply for certain posts), but these are rare and clearly stated in the official notification.

How many attempts are allowed for an open competitive examination?

It depends on the country and your category. In India, general category candidates can attempt the UPSC exam six times until age 32. OBC candidates get nine attempts until age 35. SC/ST candidates have unlimited attempts until age 37. Other countries have similar age-based limits with relaxations for reserved groups.

Are open competitive exams only for high-level government jobs?

No. While they’re most famous for recruiting top administrators, they’re also used for mid-level roles like tax officers, customs inspectors, and public health administrators. Some countries even use them to hire teachers in government schools or engineers in public works departments. The key factor is whether the role requires merit-based selection to ensure integrity and competence.

Do I need a degree in a specific subject to take the exam?

Usually not. Most open competitive exams only require a bachelor’s degree in any field. The content tested is general-history, polity, economics, current affairs-not specialized. That means a mechanical engineer, a history graduate, or a commerce student can all compete on equal footing. What matters is how well you understand the syllabus, not your major.